She would be part of the 3% of Americans listening to Arabic music…if she lived in the United States…or was real…

For the last few years, I thought the central dilemma facing the Japanese music industry was an artist problem. Contrary to rapidly-gathering-dust takes about its international chances accumulated over the last decade, the world loves Japanese songs. Whether via the discovery of city pop gems, the prominence of singles attached to anime, or Fujii Kaze’s charm, no shortage of individual numbers have climbed up various viral charts and found success across platforms. Yet building from that has been much harder…the music isn’t the issue, it’s getting people to know the people behind them.

Then with the success of “Left Right” and “NIGHT DANCER” and especially “Idol” coupled with the arrival of Spotify’s Gacha Pop playlist, I started changing my analytical tool. Maybe songs performing super well is all you need. Yet! One more pivot…after looking over Luminate’s Midyear Report for 2023, I’m convinced J-pop has pulled off a tightrope-walk between song and artist success.J-pop and Japan pops up a surprising amount in Luminate’s latest report, even getting an entire slide to itself. I’m not going to pretend like the sounds of this country are taking the world by storm — but compared to previous data points where it was but a blip and especially looking back on takes aged only a little over a year old declaring J-pop as “slowly dying,” the outlook has become much more rosy. For the first time in…hell, the first time since I started covering Japanese music in 2009, J-pop’s global potential seems to be on the rise.

The most surprising but most telling stat comes in Luminate’s section on the growth of “global” music in the United States. It’s a familiar story…pop has gone worldwide, with listeners checking out songs in languages they don’t know more than ever before. There’s a chart showing the “Top Languages for U.S. Music Listening,” and Japanese finishes with the same percentage as French…and one percentage point ahead of Korean, which is slight but still a surprise given the directions J-pop and K-pop have gone in the 21st century.

Korean still ranks ahead when it comes to “consumption” (more on that later), but the above is telling. Critically, it isn’t just about music.

Bloomberg recently wrote a feature on Crunchyroll, Sony’s anime streaming platform and “new money maker.” One of the biggest takeaways from it is that anime is now more profitable overseas than at home. I appreciate data and charts, but part of me could have guessed that from ~vibes~ alone. Always big, anime became even more omnipresent in recent years, thanks both to greater access to series and a continually evolving cool cache powered by athletes and musicians. Anime is mainstream, and one of the most popular non-US-born artistic industries in the world today, to the point where crowds at Anime Expo in Los Angeles this year look dangerous.

That’s what’s truly lifting J-pop up, at least to the levels where 8 percent of U.S. listeners are checking out music in Japanese. The opening and ending themes for these series connect with listeners even if they don’t know what the lyrics are about, and coupled with J-pop’s general embrace of streaming in recent years, they’ve become more accessible than ever. Just look at “Idol” once again, a song achieving chart milestones and YouTube-topping status this week in large part because of its connection to the most popular anime of 2023 so far.

In the past, I think the industry would bristle at this…J-pop and “anisong” were held apart from one another, with separate sections in places like Tower Records and events for the latter like the annual Animelo concert feeling like some kind of alternate pop timeline when I would go in like 2012 and 2013. Now though, they’ve embraced it to find a new path forward.I apologize for writing about Gacha Pop so much, but I think it’s a masterstroke from a presentation perspective. Take the seeming biggest weakness of the last few years — “people only know songs instead of artists,” and “J-pop doesn’t have a unified sound!” — and present them as strengths. Anecdotally, I’ve found lapsed J-pop listeners, folks focused on English-language tunes and those who have even grown cynical to music at large land on at least one song on this playlist they vibe with. Wisely, everything available online1 gets to intermingle, whether it’s from an anime or a K-pop-inspired boy group or an electronic artist or fucking Mall Boyz. J-pop is as diverse as any other music industry on Earth…so why not stumble about and find what about it you like?

Despite an emphasis on songs…a new generation of J-pop artists have emerged as global faces for the Gacha era. As Luminate points out, YOASOBI, Fujii Kaze and Ado are the top three J-pop acts in the United States, and their presence in the American market is pretty impressive, including a real strong showing in New York (New England, once again, proving they have no taste in anything). That only grows stronger when you expand to global, and zooming out also forces you to include names like imase, Official HIGE DANdism, King Gnu and more. Songs power J-pop forward internationally…but the names behind them are getting more looks now, too.

I think the next step is actually venturing into the areas where people are listening to this new crop of J-pop. That’s already underway…YOASOBI played festivals in Southeast Asia and will join XG and Atarashii Gakko! in Los Angeles later this summer, while Fujii Kaze performed intimate piano shows across Asia. Based on rumors I’ve heard from within the industry, 2024 will be an even bigger year for international shows and tours from Japanese artists. In the past, scoring a noteworthy gig in, say, the United States was like a memento or a marker to show how far an older group had come. But now, I think it will become an actual stepping stone to something more.

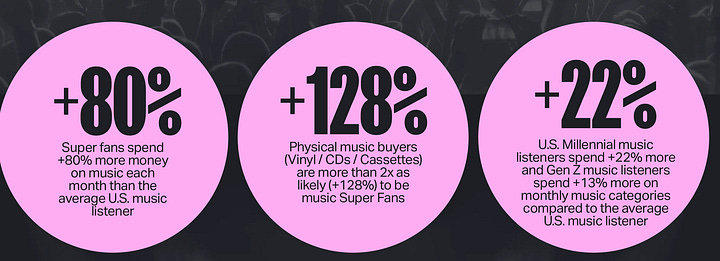

The Japanese music industry shows up all over other parts of the Luminate report too — just not directly. Instead, all you have to do is look at the “Super Fans” section of the 2023 midyear report to be reminded that, right, the music biz is currently stuck in the Oricon days of 2013 J-pop. That is to say, everything is AKB48.

I mean, half of these were trotted out a decade ago to explain why Japan was a backwards-ass nation. Now, “super fans” are an essential part of the global music industry, as is there devotion to purchasing physical media that was formerly a punchline. It’s a sign, as so many developments in general have shown, that shifts in Japanese culture (pop or otherwise) tend to predict great global shifts. Back in 2013, critics said AKB48 were gaming the system by selling primarily to a hardcore niche of super fans rather than the general public, distorting the vision of what was actually popular. In 2023…that’s the whole global industry.

Similarly, scroll down to the midyear song / album rankings and soak in just how fragmented everything is — streaming audio is different than streaming video which is different from what’s played on the radio and we aren’t even getting to physical yet, which we’ve established is important again. It’s Oricon in the mid 2010s all over again, when a single chart leaning on one primary metric failed to accurately capture the pop landscape, when in reality you had to divine between like six. The Luminate list underlines this is happening…has been happening…on a greater scale too.

So…is it possible Gacha Pop could be a glimpse of a greater future? To some degree, the concept (and J-pop in general, at least the stuff actually connecting abroad) stands as a counter to “super fandom,” offering surprises and discovery instead of an otaku-like obsession with a solo group. That’s shaken up a little by the anime connection — I mean, talk about otaku — but still the concept also makes room for the CHAIs, Haru Nemuris and Pasocom Music Clubs of the world.

If the global music industry is going through its “Theater Edition” era, what comes next? Maybe Japan is a good example, where “super fans” still have their space, but thanks to the acknowledgement of the fragmented landscape, more artists have the chance to find space and connect. Gacha Pop isn’t a genre…it’s a concept to work with, and shows anything can change with enough time.Written by Patrick St. Michel (patrickstmichel@gmail.com)

Twitter — @mbmelodiesFollow the Best of 2023 Spotify Playlist Here!

I think this point can’t be stressed enough, and plays a huge role in pushing the concept of “Gacha Pop” as something new in the context of J-pop. This is a new era of music, and if you aren’t on the platforms hosting the music, you aren’t going to be part of the new wave. So…sorry Johnny’s groups save for Travis Japan (mandated to be on Spotify thanks to Capitol Records), you were the old-school anchor of J-pop, but you aren’t around these parts so you’re out…maybe YouTube Music can think of something to help you out. It’s almost a restart, and a chance to redefine what J-pop should get attention.

I think another possible reason for the growth of J-Pop in the west is that many K-Pop fans such as me, Nick of TheBiasList etc., are hearing more and more J-Pop. Many of the older fans kind of enjoy discovering new music. Additionally, the metalheads are discovering J-Pop as well.