Make Believe Mailer 74: Continental Drift

Yuka, imase, And Where Popularity Comes From In The 2020s

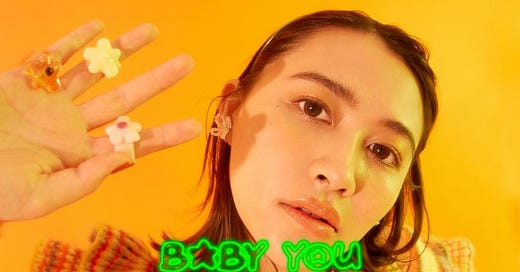

Singer/songwriter Yuka’ career up to her major label debut was painfully Millenial — aspiring artist who kept failing auditions and talent contests turn to social media to share covers of songs with originals sprinkled in, building an audience from the safety of online uploads. She parlayed that into live performances and then tours, built around cozy numbers tied to life milestones, catching attention thanks to a birthday song (“Birthday Song”).

Yet it was pure Gen Z chance that altered her path. Yuka scored a viral hit in 2022 with “Partner,” a wool-sweater of a pop song, thanks to a hand-centric dance thought up by users of TikTok (certainly helped by an official video shot from an iPhone’s POV). That surely played a role in the 28-year-old artist making her major label debut earlier this winter with Nippon Columbia, though I doubt they expected first single “Baby You” to pull of what it has in just a few months.

Thanks once again to the hands of TikTok users, “Baby You” spread across Asia. Yuka’s major-label debut shot into the top-ten viral streaming charts in Malaysia, the Phillippines, Thailand, Singapore and more — and it’s hanging around. The success at one point nudged “Baby You” into Spotify’s Global 50 Viral, and it still sits in the top 100. The Manila Bulletin reports that “Baby You” has amassed over two billion vies since coming out, when crunching all the numbers together. I think it’s just as impressive The Manila Bulletin covered it in the first place.

This is the new normal for J-pop, whether it be early TikTok-powered hits like “summertime” by indie-pop staples evening cinema and cinnamons, resurfaced sensations from the likes of Miki Matsubara, or Fuji Kaze suddenly becoming a new-era J-pop force in Asia thanks to short-form video. Japanese songs excel in a fragmented ecosystem, and anything seemingly can become a hit if the right ears (or hands) come across it.

What did feel different — the music industry was on top of it right away. Before, a viral hit like this on whatever platform would be met with surprise, but very little action to build on it at the pace internet life demands. Even in recent years, as the Japanese pop apparatus awoke to digital, a TikTok success abroad would require planning on next steps, which could go on a touch too long.

But I observed first hand a change in attitude— it was Nippon Columbia that reached out to me, stats at the ready, seeing if any kind of profile or interview in English media would be possible. This continental hit has seemingly turned Yuka into a priority, and forces are moving faster than I’ve ever seen to try to do something with it. “Baby You” is a surprise as a stand-alone song, but it’s success speaks to a bigger shift playing out with J-pop.

Via Luminate

The promise of “J-pop finally breaking through” has been rolled out for…lord knows how long, I’ve seen it constantly since I started covering Japan’s music industry (I’ve probably contributed to some of those hopeful packages!). Entertainment data company Luminate (formerly Nielsen) offered the latest iteration of this forecasting as part of their “Tuesday Takeaway” newsletter1, written by Alexandra Chan. The screenshot above offers a good overview — numbers are up across the board, thanks partially to the influence of anime. The rest of the post digs into how various J-pop acts are embraced globally compared to at home, followed by a look at the passion J-pop fans have for supporting artists, both in ways worth celebrating (most likely to buy CDs and records!) and ways more, uhhh, complicated (most likely to buy NFTs...). It ends by bringing K-pop into the mix, usually a recipe for lazy writing, but here with a welcome (and accurate) twist...turns out K-pop and J-pop fans aren't all that different.

I remain skeptical of a wide-scale phenomenon akin to the branding brilliance K-pop pulled off. Since 2020 though, I’ve adopted an optimism towards J-pop’s opportunities abroad not far off from what Chan presents. While she focuses on data and broader cultural developments (anime, which, obviously, the biggest driver, but not the only one!), I’ve been just as convinced by what I’ve seen happening inside the companies and agencies themselves. They’ve become, in most cases, more open to access and collaboration. Fears less than a decade on have receded, in favor of something approaching an honest-to-goodness attempt to go outward.

Live clip used becuase the “short MV” version of the song on YouTube remains region blocked

“Baby You” reminds me of “Torisetsu,” 2010s superstar Nishino Kana’s achingly twee 2015 megahit. The title roughly translates to “Instruction Manual,” and the song finds Kana presenting her own personal directions to a new lover to help them understand her better, like she’s a washing machine or something. This conceit — a guide to understanding me — mutated into a meme, with people on YouTube and Twitter sharing their own “Torisetsu,” some earnest and others as goofs. It’s cutesey but open for customization, while also sounding as cozy as a wool-knit top feels.

That song, though, represents mid 2010s J-pop mindsets. It was inaccessible online even to people in Japan, let alone those abroad. Despite generating personal reworks of it, nobody involved with “Torisetsu” seemed to really care or play up the greater interest. Nishino Kana was already a star…this was just a happy little internet thing, right? No need to push further.

“Torisetsu” is important because it’s an early example of J-pop being built for the social media age — I can picture the hand routines tweens would do to this on TikTok2 — and also one of the last viral hits to be gatekept by the industry. An actual history of what comes next could fill a pocket-sized book — “Koi,” Pikotaro, DA PUMP, city pop surprises, Attack On Titan themes, Fuji Kaze, etc etc. — and while it was hardly neat it all signaled a shift.

Unless you’re talking Johnny’s groups3 or like Tatsuro Yamashita4, J-pop has never been more readily available on streaming than now. And in the fragmented musical landscape of today, that's all you really need to be — present, because there's so many ways to register success and build on those victories. It actually resembles mid-2010s Japan, where the Oricon Charts became a joke, and to get an actual sense of what was popular required digging into myriad places. That's the global music industry now5, and Japanese music can flourish in all kinds of way outside of traditional Billboard success. XG made history earlier this spring by becoming the first J-pop girl group to enter U.S. pop radio's top 40. Definitely impressive! But what about when compared to YOASOBI’s “Idol” pulling in over 86 million views on YouTube? Or, to get really current, EHAMIC’s Vocaloid number “Koinu No Carnival” jumping to number one on the Spotify Global 50 Viral Charts, thanks to an appearance in the newest Guardians Of The Galaxy movie?

All of those are signs of J-pop’s legs abroad, but they are also a bit chaotic. Which is the natural state of music today. While the West remains the ultimate siren song for Japan’s music industry, it isn’t the place best underlining changes in J-pop’s perception. That’s happening much closer to home.

J-pop upstart imase scored one of 2022’s bigger surprise hits with “NIGHT DANCER,” a zippy single performing wildly well on TikTok. Like so many other Japanese performers, it spread via the short-form video site abroad. Unlike most, it ended up a viral hit where Japanese songs usually don’t excel.

“NIGHT DANCER” blew up in South Korea. It wasn’t even a cute meme uptick that lands something on a “viral” ranking — “NIGHT DANCER” became the first Japanese song to ever land on the country’s Melon chart, peaking at #17. It was enough of a sensation where imase traveled to Seoul to put on a special concert, and perform on top of a sightseeing bus (above).

He’s managed the most chart success, but South Korea has become a great example of a resurgence in J-pop across the continent. Publication Sports Seoul observed as much in a recent column (translated into English over at Nante Japan), noting a boom in J-pop among younger Koreans primarily thanks to a (surprise) love of anime / manga along with a general increase in Japanese tunes performing well on short-form video platforms like TikTok. Check out the Spotify Top 50 chart for South Korea, and you’ll find a smattering of songs from YOASOBI (top ten), imase and Aimyon6. That’s the top-tier ranking too…look at the viral and prepare to see an even greater global mish-mash. The songs are out there...listeners do the rest.

The West will — for better or for worse — forever be this gleaming diamond entertainment companies around the world covet, even while equal if not more treasure surrounds them. Such is the case with the Japanese music industry and people following it, which will always wonder “how to break it in America” and guffaw at its shortcomings.

But Asia is the foundation for this 2020s growth in J-pop outside of the country, and I think labels, artists and companies realize it now. Fans in South Korea flocked to imase…so he went to them. The continent went gaga for Fuji Kaze, so he’s bringing his first international tour to the region around him. Yuka’s debut blossomed in Southeast Asia…and yeah, her label is going to reach out to one of the three English-language writers covering contemporary music in Japan today7, but they also know where the action really is.

Critically, gaining momentum in Asia can catapult a song or artist further. With imase, you can find “NIGHT DANCER” sneaking into viral charts across the world, especially in South America. That’s because of all the trends born in Asia, eventually spreading. This is just the trajectory of short-form dances and meme-ry…emerge from somewhere, flow outward. Yet Asia — because of both a love of Japanese pop culture at large and music that is able to stand out, even if it does so in minute-long bursts8 — embraces it first, and helps share it from there.

Here’s an AiNA THE END song performing well in Taiwan, I think because of Gundam.

The beauty of the current regional pop landscape is that Japan isn’t unique here — there’s so much criss-crossing and collission happening across the continent. Korean teens might be embracing “NIGHT DANCER,” but their Japanese counterparts are just as mad about “Cupid” as the rest of the world. Both are probably not far off from joining Southeast Asia in dancing along to a cover of early Aughts Thai helium-filled dance-pop. There’s more collaboration between artists and greater chances to perform abroad. K-pop continues to lean into diverse lineups of performers from across Asia, as the recently announced BABYMONSTER remind.

J-pop loosening up a bit and letting songs travel more freely…and be reworked by fans how they see fit…has been huge, but just as important has been industry players themselves actively following up on these developments, and especially keeping a close eye on Asia. America remains a prize, but people here are realizing that putting a focus on the audiences around them can be a step forward.

Written by Patrick St. Michel (patrickstmichel@gmail.com)

Twitter — @mbmelodies

Follow the Best of 2023 Spotify Playlist Here!

Forwarded to me by Tamar Herman, whose Notes On K-pop is an essential subscribe for anyone reading this newsletter (and anyone with interest in Asian pop at large).

Of course, this happening today is totally within the realm of possibility.

Though worth noting…you can actually access their work through YouTube Music, it’s just that Spotify has carved out such a place in people’s minds that this isn’t satisfying for the people who want to hear SexyZone all the time.

An artist very aware of how many CDs and records J-pop fans buy, and is no rush to change.

The best example of this actually comes from K-pop in 2023. BTS member Jimin’s “Like Crazy” topped the Billboard Hot 100, a historic accomplishment and as traditional a mark of success as you could find in music. But then…it made more history the next week thanks to the biggest drop from the top spot ever (everything is AKB48). It certainly did well and still has legs elsewhere…but nobody would call it the biggest K-pop hit of the year so far. You would have known that title belonged to FIFTY FIFTY’s “Cupid,” if you followed TikTok and viral charts and weirdo AI YouTube accounts where they make rappers “cover” it. Now, it’s actually bumrushing Billboard…though, in a twist, that’s partially because of the existence of an official English version and official sped-up version (everything is AKB48…even online).

Have mentioned this before but relevant here — the Aimyon song blowing up in South Korea comes from her 2017 album Excitement Of Youth, the full-length that taught major labels streaming could be beneficial for them because it was like, a top-five hit for a year and a half afterwards.

uhhhhh if you want an interview with Yuka, I can hook you up.

And also…uhhhh I’m probably not the one to dwell too much on this, but the image of Japan in the region is pretty swell at the moment. Like, there’s probably an academic paper to be written connecting the success of “NIGHT DANCER” with improved diplomatic ties between Japan and South Korea.

To be honest, this is the first I’ve heard of Yuka—and you cited the Manila Bulletin, which means it’s already something here! That says a lot about my bubble, I suppose. This has been a very good read!

Suddenly I’m entertaining the idea of having Yuka for this feature I’ve been cooking up the past few months, haha. Don’t always punch above your weight, Niko!