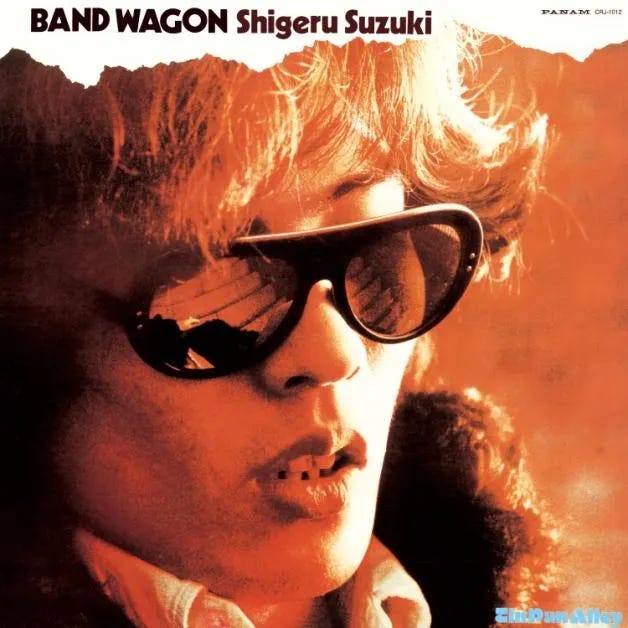

Make Believe Mailer #140: Band Wagon

The First Solo Album From A Prolific Guitarist...Or The Secret Last Album From A Vital Band???

Part of the thrill of discovering Japanese music from the 1970s and ‘80s is the all-star collaboration on display within even the most ho-hum albums. Check the credits section of any insert or Discogs page and prepare to be blown away by legends of pop, “city pop,” “new music,” funk, “disco, fusion and beyond intersecting. In time this sort of pop cross-pollination would become rarer, but in the ‘70s particularly the community of like-minded creators was small…and they all played with one another. It’s key to the era’s charm.

BAND WAGON exists as an outlier. Shigeru Suzuki allegedly called the way his first solo album was recorded a “betrayal” to the members of Tin Pan Alley, the hit-making group the guitarist joined after the end of his first outfit Happy End alongside fellow member of that influential group Haruomo Hosono, drummer Tatsuo Hayashi and keyboardist Masataka Matsutoya. For his full-length debut, Suzuki went to the west coast of the United States, splitting time between San Francisco and Los Angeles, working exclusively with American players.

For the celebrated and prolific Suzuki, this venture would end up being a one-time affair — already active as a session player for Japanese acts galore in the early 1970s, he’d only pick up the pace after BAND WAGON’s release, which marked its 50th anniversary a few weeks back. Seriously, just look at his Discogs “Credits” page. He also kept relesing solo material, but never again decamped to the States, but rather working with compatirots in the blossoming Tokyo music scene (including heavy contributions from Ryuichi Sakamoto for 1978’s Telescope).

It makes his very first album all attributed to him extra interesting — it’s every bit of part of the 1970s Japanese canon, but coming together outside of it.

Recently released 50th anniversary edition of BAND WAGON

In Suzuki’s oveure, BAND WAGON finds him in a bit of a transitional period. The highlights are among the best songs he’s ever done out on his own — the jazzy skip of opener “Suna No Onna,” the funk rumble of “Bintetsu Shonen,” the roomier noodling of “100 Watt No Koibito” — but it also leans a little too much into American blues rock and, worst of all, crunchy jams. I’m personally more fond of his latter releases, with follow-up Lagoon delivering the easy-breezy beach vibes I prefer while his latter day Sunset Hills Hotel series exists as his most fascinating detour and a great example of an established musician taking full advantage of his friend circle (calling on Seiko Matsuda…to compose an instrumental?!?!).

BAND WAGON, though, is the chance for Suzuki to geek out over American rock, and with this cast, who can blame him? Members of Little Feat, Santana, Tower Of Power, Quicksilver Messenger Service and more helped make his debut possible. Seeing as Suzuki loved west-coast American rock as he matured into a guitarist himself, it’s easy to imagine how thrilled he must have been to have this opportunity.

He’d never really do it again — as happened regularly later in the decade, an occassional American player would find themselves in Japan and play on some of his albums — and nearly no Japanese artists from this fertile period ever tried something similar. BAND WAGON exists as a kind of sonic puberty for Suzuki, and an interesting entry into ‘70s “new music,” finding one of its biggest names heading to California to imagine life as a west coast dude. There’s nothing like it.

Well, except for another album Suzuki played on.

BAND WAGON does feature heavy contributions from one other Japanese artist — Suzuki’s former bandmate in Happy End Takashi Matsumoto. According to the drummer and prolific lyricist, Suzuki let him go wild with the words — Suzuki has always been a guitarist first, and has been happy to cede lyrical duties over to those he trusts, which primarily means Matsumoto. According to a 2024 interview with the two, Suzuki would go over lyrics with Matsumoto on the phone from California…wracking up a massive phone bill.

Perhaps not the best financial move, but one that makes sense given what came before BAND WAGON. Everything about Suzuki’s debut flows downstream from Happy End’s self-titled farewell, which found the quartet recording in Hollywood with many of the names who would also appear on their guitarist’s first solo offering. When I talked to Matsumoto and Suzuki for The Guardian in 2024, the prior believed all four members were thinking about their next step career wise, while the latter was thrilled by the chacne to go abroad. “Recording in the U.S. was a dream come true,” Suzuki said.

He still leaned on Matsumoto to write lyrics, but work on Happy End (1973) seemingly instilled a newfound creative confidence in Suzuki, as he sounded more active in contributing his own ideas and served as a kind of team leader to keep everyone else — with all kinds of other opportunities in front of them — focused. I think it’s safe to say that recording gave Suzuki confidence to go even further. Which I think explains why he practically recreated the setting, contributors and sound of the final Happy End album for BAND WAGON. This was his period of growth…he wanted to revisit it, but just by himself (and some costly telephone calls).

It’s this perspective that makes me think of BAND WAGON not so much as Suzuki’s first proper album, but as Happy End’s true finale. Sure, the full band isn’t there — Eiichi Ohtaki linked up with Tatsuro Yamashita and others to fine-tune his pop visions in 19751, while Hosono turned away from his bedroom folks to start exploring his concept of “soy sauce music” on one of his most adventerous albums ever2 — but the truth is neither shaped Happy End that much, with Hosono eyeing what came after and Ohtaki literally forgetting to do anything for it.

Matsumoto and Suzuki did a lot of heavy lifting on that final band album, and it all carries over to BAND WAGON, which Matsumoto described in the above interview as offering him a chance to play with more Happy-End-style lyrics one last time. Suzuki, meanwhile, comes off as someone building off his past experiences3, making an album not far removed from Happy End’s ending but with more room for him.

Again, I think Suzuki would go on to grow much more confident and offer his own perspective in the years ahead. BAND WAGON is the sound of him revisiting his first artistic growth spurt and recapturing the experience to help him become a fully fledged creator. A young creator would rarely go to another country by themselves unless they really wanted to capture a specific vibe, and for Suzuki, I think it was the same one as on 1973’s Happy End, which echoes through his debut.

Written by Patrick St. Michel (patrickstmichel@gmail.com)

Twitter — @mbmelodies

Check out the Best Of 2025 Spotify Playlist here!

though, should be noted, featuring Suzuki…who kinda feels like the glue across all three other member’s ‘70s output.

I will definitely write about this one, as it is 1. my favorite Hosono solo offering by a pretty wide margin and 2. a contender for greatest Japanese album of all time, in my little opinion.

Bonus points for not having a drunk Van Dyke Parks come in for these sessions to talk about Pearl Harbor with the members.