Make Believe Mailer 19: Opening Ceremony

Inside: What It Feels Like To Dine Inside The 1964 Athletes' Village

Part One In A Series On Japanese Music And The Olympics

The 1964 Olympics are generally looked back on as a turning point for post-war Japan. Emerging out of the ruins of World War II, the Summer Games — held in the fall due to intense summer heat — weren’t just an opportunity for the once-Imperialistic nation to re-emerge onto the global stage with a new image, but a literal transformation of everything. The Shinkansen debuted as did the Budokan (this doesn’t exist without the Games), while host city Tokyo started to resemble the metropolis it is today, thanks to non-stop construction and revitalization in the years leading up to the event.

It’s maybe a little too cute to say this Olympic-powered transformation literally impacted all art out of Japan in the years after, including music. Tokyo has shaped the sound and image of songs all the time, and this Tokyo emerging in 1964 is the one that shapes ‘70s “new music,” that provides the glitzy excess of “city pop” and other ‘80s offerings (not to mention the fake memory of the capital latched on by people today), the continent-hopping cool of Shibuya-kei in the ‘90s and even the more glum post-Vocaloid hits of now.

“It’s kind of hard to say, because Tokyo was all I ever knew. It’s tough to pinpoint something specific about the influence, as I was born and raised in Tokyo. But things drastically changed after the 1964 Olympics were held here,” Taeko Onuki told me a few years ago. “They tried to set up a much more intricate infrastructure for the city at that time, and a lot of things got destroyed and things like highways were built. Express trains started running on the Inokashira line, from Kichijoji to Shibuya. It was so strange and mysterious – why do you need to be in such a hurry? Everything became so busy, and it became more and more difficult to just live. And it only grew tougher heading into the Bubble years of the 1980s.”

Taeko Onuki, “Tokai,” a song about the challenges of Tokyo life

To just zoom in on the 1964 Olympics themselves, however, reveals a lot of musical developments that would later blossom into something more, or at least served as grand-scale examples of trends still going today.

Let’s start with one of the more notable debuts that year — electronic music. Based on write ups and reflections of the Opening Ceremony, one of the first musical cues of the afternoon came courtesy of early electronic composer Toshiro Mayuzumi. “Olympic Campanology” came together at the NHK Electronic Music Studio, an early Japanese source of experimentation in this field (think a slightly more buttoned-up BBC Radiophonic Workshop). The Games gave Mayuzumi and company a chance to share their work on a greater platform, for the occassion cutting the sound of bells with the noises they generated, combining them into something formerly unheard. Imagine hearing this echo in the National Stadium.

“I wanted to try and express the spirit of the Japanese people, a spirit derived from Buddhism. Since bells are a symbol of the Buddhist religion,” Mayuzumi said in an interview. “I recorded the sound of sacred bells at temples at Nara, Kyoto and Nikko. These were then fused with the pure tones produced electronically.”

“Olympic Campanology” also represented a slight thematic tension underlining not just the Opening Ceremony but the whole Games — what, exactly, was Japan going to push forward as its image at this moment? Read that linked article above, and you’ll see that other composers weren’t as keen to dip into the country’s historical sound — more Japanese people were embracing Western styles, so why pretend court music was still the dominant flavor?

Then again, the lead up to the Olympics saw hit songs embrace classic forms rather than emerging rock (or “group sounds”) styles. In Japan, the pre-Games smash was the theme song “Tokyo Olympic Ondo,” released in 1963 in numerous forms, but most connected with singer Haruo Minami. That one was such a memorable tune that, decades later, when people wanted to feel all tingly about this epoch-shifting event, they brought Minami out to perform it.

Something similar was happening abroad — that same year saw Kyu Sakamoto (who also tackled the Olympic theme) make history as the first Asian artist to top the Billboard Hot 100 with his song “Ue Wo Muite Aruko,” a keep-your-chin-up protest song reflecting ongoing student demonstrations. Of course, it didn’t achieve commercial success outside of Japan because of that, but rather becuase it was re-named “Sukiyaki” and sold as Oriental kitsch to Western audiences, building on the popularity of “exotica” music as pioneered by Martin Denny and others. While starting to fade by 1964, there was still space for an imagined East come the Games.

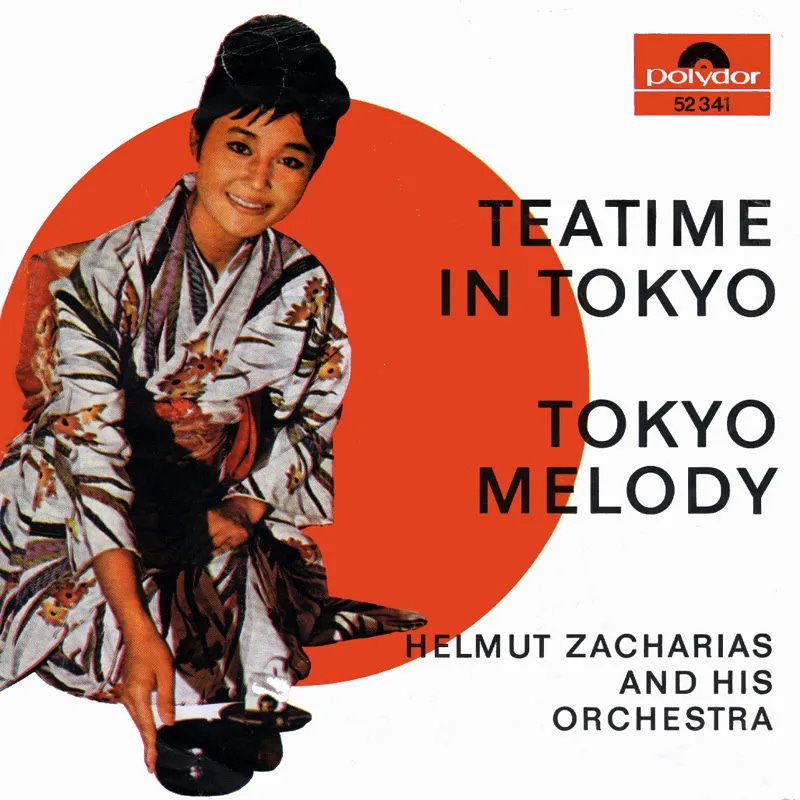

German composer Helmut Zacharias made a whole album of Japan-inspired tunes, with names like “Sakura Sakura” or outright covers of “Sukiyaki.” The above “Tokyo Melody” gained special attention in the U.K. after BBC selected it to be the theme song for their Tokyo Olympics coverage (the first Games to be broadcast live on TV). It charted in the top ten. While not quite the fantasized image of Japan lurking in exotica music — the b-side comes way closer to that — “Tokyo Melody” does still indulge in a little bit of Orientalist fantasy, with an Asia-inspired melody propelling it forward. The first satellite-broadcast Games also meant people around the world could see a far off place, but the surrounding accoutrement could still play with an imagined idea of the country.

I don’t know if “Tokyo Melody” counts as the biggest moment of this sort of Western interpretation of Asian music, but it’s up there with Denny’s exotica boom and “Sukiyaki.” In the wake of the Olympics, a new kind of artist emerged in Japan, highlighted by Haruomi Hosono and Ryuichi Sakamoto among others, who played around with this exotic image of Japan and flipped it on its head. Yellow Magic Orchestra flipped Denny specifically, but I think it’s fitting that a 1985 documentary all about Sakamoto is titled Tokyo Melody — it exists in the same space they looked to play in.

How Japan is seen through music by those outside of the country today has changed drastically — the exotic sounds of yesteryear have been replaced with a memory of dazzling wealth and good times via the interest in “city pop.” Where that boom exists in bright Technicolor, its cousing “ambient music” sits in a corner wearing a turtleneck sweater. “Environmental music” or “Kankyo Ongaku” has enjoyed its own re-discovery in recent years, with a focus on how pieces filed under this term were deployed in physical spaces (from exhibits to MUJI).

Yet you can trace this back to the 1964 Olympics as well (as noted in Light In The Attic’s book accompanying their “Kankyo Ongaku” comp from a few years back). Kuniharu Akiyama composed music for a pair of dining rooms used by the athletes at what we’d today call the Olympic Village. As not to just repeat better sources, you should read the Soundohm write up of the album, which goes into how Akiyama put it together (stones! so many stones, mining them too). Then imagine being, like, a high jumper trying to enjoy breakfast and hearing this music. Most have been wild.

It’s just another example of just how far the reverberations — stone-generated or otherwise — the 1964 Olympics go. The 2020 Olympics clearly tried to recreate the same society-shifting moves those first Japanese Games did and maybe if COVID-19 never happens, they would have managed something similar, both domestically and internationally. That’s all hypothetical now, but if 1964 shows anything, it could have been a possibility.

Written by Patrick St. Michel (patrickstmichel@gmail.com)

Twitter — @mbmelodies